Column

Report

Big picture issues, big picture ideas and data

It seems you can’t turn on the evening news or open up a newspaper in Canada without seeing a story about climate change. Similarly, stories about oil and gas development in Canada (especially pipeline stories), and carbon taxes have garnered significant political discourse over the past few years.

With that in mind, we wanted to pull together some data and information related to some big picture questions about those inter-related issues:

1) Where does Canada fit in the global discussion about climate change?

2) Where does Canada fit in the global oil and gas picture?

3) What does Canada’s carbon tax policy look like?

4) How does technology affect these three issues?

To be clear, climatology is not an area of expertise at SecondStreet.org. Therefore, we’re not going to debate mankind’s impact on the Earth’s climate. We’ll leave that up to scientists. This post examines the aforementioned issues while taking into account the reality that political parties across Canada’s political spectrum are committed to reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

Our goal with this post is to pull together information that the public, and policy makers, might find useful.

WHERE DOES CANADA FIT IN THE GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE DISCUSSION?

According to the federal government, Canada produced 716 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2017. This is up from 602 megatonnes in 1990, but slightly lower than Canada’s peak of 744 megatonnes in 2007.

The federal government’s website notes that Canada’s emissions represented approximately 1.6% of global emissions in 2014. While Canada’s total emissions are small on a global scale, on a per capita basis, research suggests Canadian’s emissions are in the top three in the world. This is largely due to our climate (we need to generate a lot of heat in the winter) and the size of our country (we burn a lot of fuel getting from city to city and transporting goods between communities).

Where do Canada’s emissions come from?

In terms of where Canada’s emissions come from, this government of Canada web page has some useful data. It shows that our emissions are derived from five main areas:

40% – Industry

25% – Transport

13% – Forestry, agriculture and waste

11% – Electricity

11% – Homes and buildings

If you’re looking for a breakdown of our emissions by industry, this government of Canada web page has some good data:

Oil and gas: 27%

Transportation: 24%

Buildings: 12%

Agriculture: 10%

Heavy industry: 10%

Electricity: 10%

Waste and others: 6%

Canada’s emissions vs the world

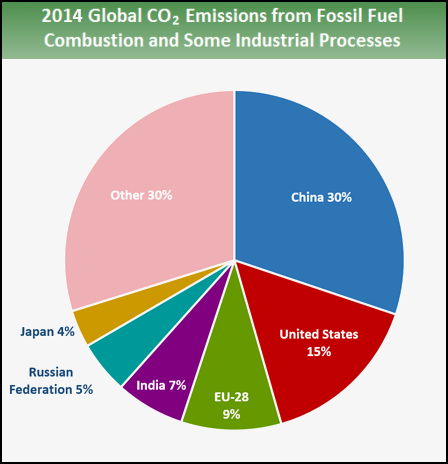

This graph from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency summarizes where global emissions originate. Notably, China, the United States and India represent roughly 52% of global emissions. If we include Russia and Japan, the total rises to 61%.

In terms of Canada’s commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, back in 2015, Canada’s federal government committed to reduce emissions 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. While that commitment was made by the previous government, the current government has maintained the target.

What’s interesting to note is that if Canada went beyond our 30% emission reduction target, and somehow completely eliminated all of our greenhouse gas emissions, based on the pace global emissions grew between 2005-2014, all of our efforts would be eliminated in a single year as emissions from other nations rise.

With this in mind, there are three important points to consider:

a) If the rest of the planet does not reduce emissions in a meaningful way, then it’s fruitless for Canada to reduce our emissions; Canada’s emissions are negligible in the grand scheme of things.

b) If Canada takes action to reduce emissions, and the rest of the world does not reduce emissions in a meaningful way, then we could be caught unprepared and having to cope with the effects of climate change (floods, drought, etc.)

If the world is not going to meet climate change targets, it may make sense for Canada to spend funds on adapting to climate change (eg. building flood infrastructure, sea walls, etc.) rather than on expenses to reduce emissions.

c) If the rest of the world is tackling emissions in a meaningful way, then it’s completely reasonable for Canada to pull its weight.

WHERE DOES CANADA FIT IN THE GLOBAL OIL AND GAS PICTURE?

According to the federal government, Canada has the third largest proven oil reserves in the world and was the fourth largest producer of oil in 2017.

In terms of natural gas, our nation was the fourth largest producer of natural gas in 2018 and is the fifth largest exporter.

Combined, Canada’s oil and gas sector represented about 6.3% of our nation’s economy (direct GDP) in 2017 and employed 533,000 people in direct and indirect jobs.

To see an example of how intertwined the industry is with the rest of our economy, see this SecondStreet.org clip with Jocelyn Bamford from Automatic Coating Limited, a Scarborough company:

While Canada has a large amount of oil reserves, most of it is located in Alberta and Saskatchewan; 93% of our production comes from these two provinces. As our nation does not have enough pipeline capacity to transport oil from western Canada to eastern Canada, we imported approximately 592,600 barrels of oil per day in 2018; most coming from the United States (64%), Saudi Arabia (18%) and Azerbaijan (6%).

In terms of total energy use in Canada (hydro, oil and gas, nuclear, solar, etc.), the federal government’s Energy Fact Book estimates that approximately 70% came from the oil and gas sector in 2017. Thus, “keeping oil in the ground,” as some advocate, would have a seismic effect on our lives in the short to medium term and is unrealistic.

But not only is oil used for transportation, heating our homes, creating electricity and other energy purposes, there are all kinds of products that are derived from oil. This blog post – click here – has lots of information on such products that we use on a daily basis; plastics that make components for cell phones, aspirin and materials used in bicycle tires to name a few.

Global Demand

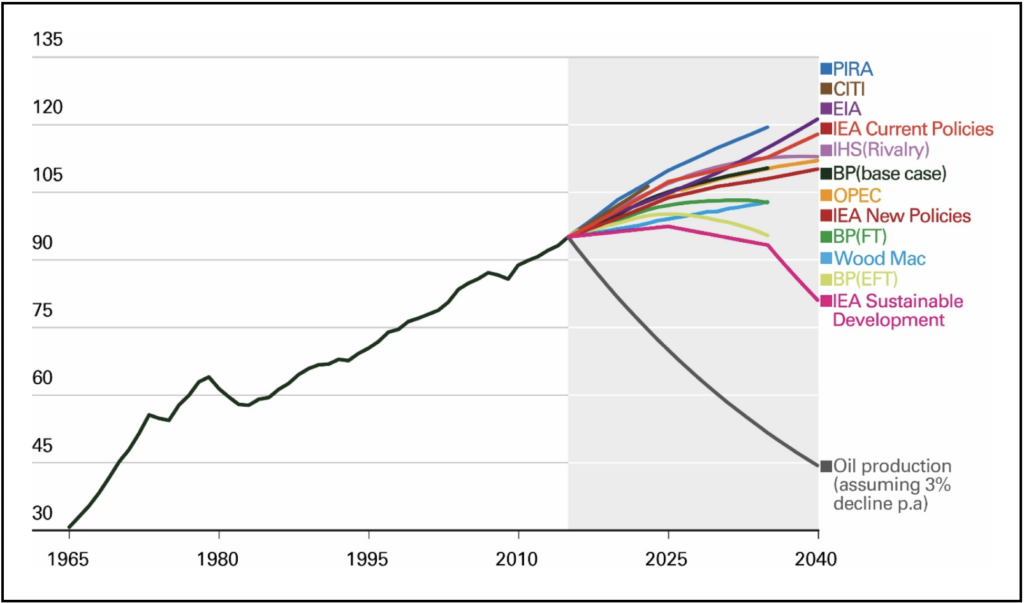

When it comes to forecasts for global demand for oil going forward, one of the best sites we located was BP’s (formerly known as British Petroleum). As you can see in the graph below, BP gathered eleven different forecasts for future oil demand and plotted them:

Of the eleven projections, nine expect global demand for oil to increase at least until 2030. Of the six that projected demand out to 2040, five suggest demand will grow until at 2040. Analysis recently released by the United States government estimates global oil and gas usage will increase at least until 2050.

A forecast put forward by the International Energy Agency (based in France) also projected long-term demand to increase, but noted something interesting – electric cars may lead to a slowdown in gasoline use, but petrochemicals and jet fuel will still drive overall demand higher. (Petrochemicals are derived from oil and are used to make cell phone parts, bicycle tires, running shoes and many other household and industrial products).

Thus, a key question for Canada in all this is – as the world continues to buy more and more oil, should Canada provide it or should we sit on the sidelines and let some other country sell that product and enjoy the economic benefits?

Extreme environmentalists will bristle at this reality, but keeping Canadian oil in the ground won’t actually help the environment. If we don’t provide the world with the oil it continues to buy, some other country will simply increase production.

One need only look south of the border to see how this could play out.

In 2008, U.S. oil production was approximately 5.00 million barrels per day. By 2018, the U.S. had increased production to 10.99 million barrels of crude per day; a 120% increase.

If Canada sits on the sidelines and slows production, there’s no reason to expect that the United States or some other country wouldn’t provide the extra oil the world wants to purchase.

The U.S. is Taking Advantage of Canada

A key consideration in the discussion about Canadian oil and gas resources is something few Canadians know about – the United States has been taking advantage of our country’s oil predicament for years.

The problem is related to Canada’s severe lack of pipeline capacity to our coasts. While Canada has many pipelines that transport oil to the United States, our inability to get oil to the coast means we can’t ship it to China, India and other countries in a meaningful way. As a result, 96% of the oil that is exported from Canada is shipped to the United States.

The United States in turn takes advantage of the situation, routinely paying Canada far less for each barrel of oil than what they pay U.S. producers. Why? Partially because the U.S. knows our industry doesn’t have other options.

This price discount between what U.S. producers receive (known as West Texas Intermediate: WTI) and what Canadian producers receive (Western Canada Select) is known as the “differential” and it costs Canada’s economy, Canadian businesses and Canadian governments, a substantial amount of money each year. This Alberta government web site – click here – shows the differential over several years. In July 2019, the U.S. paid an average of $44.70 per barrel of oil from Alberta while it paid U.S. producers $57.35 per barrel. That works out to a differential of about 22% lower.

At times, the differential can be even more severe. In December 2018, the U.S. paid $49.52 per barrel of oil from other nations while only paying Canada $5.97 per barrel. That’s a price discount of 88%.

To be clear, there will always be some price difference between Canadian oil and oil that’s produced in the United States. This is due to the cost of transporting oil from Canada all the way to refineries in the southern part of the U.S. Further, the quality of U.S. oil is higher than the oil that’s coming out of Alberta. (See this Alberta government post for more information about the differential).

What construction of pipelines to the coast (eg. the Trans Mountain pipeline, Energy East Pipeline, etc.) would do is reduce the differential as it would allow Canada to export petroleum products outside of North America and reduce export dependence on the United States.

Consider, a November 2018 Scotiabank report that estimated a lack of pipeline capacity will cost Canadian oil and gas producers between $15-39 billion in 2019 and the Alberta government $1.5-4.1 billion in lost royalty revenues ($350-950 per Albertan). In addition to missed royalty revenues, governments would also miss out on personal and corporate income taxes; something that’s not included in Scotiabank’s estimates. Governments could use the additional revenues to pay for infrastructure, repay debt, reduce tax rates and more.

The Canadian Taxpayers Federation estimates that a lack of pipeline capacity cost the federal government $6.2 billion between 2013 and 2018 (roughly $168 per Canadian).

For producers, reducing the differential would increase profits, providing them with more funds to expand and hire more workers. A higher price for Canadian oil would also encourage more producers to expand into the Canadian market.

Pipeline safety:

A key question about transporting oil, especially after the Lac Megantic disaster, is safety. With that in mind, the government of Canada notes the following on its website:

“Pipelines are a safe, efficient and reliable way to move Canadian energy to consumers. In 2015, almost 1.3 billion barrels of crude oil and petroleum products were safely transported by Canada’s federally regulated pipelines. On average each year, 99.999 percent of the oil transported on federally regulated pipelines moves safely.”

The Fraser Institute examined government of Canada data and concluded that transporting oil by rail was 4.5 times more likely to experience a problem.

Pipeline Emissions:

Speaking to the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, Chief Mike LeBourdais of the Whispering Pines-Clinton Indian Band (BC), noted something interesting about pipelines:

“Pipelines don’t create climate change, actually they reduce it. When you’re trucking oil by rail or truck you are increasing CO2 emissions. However, First Nations understand that the environment is the important part so if you want to protect that you use oil pipelines rather than rail or truck.”

This assertion is backed up by a University of Alberta study that found pipelines produce between 61 and 77 per cent fewer emissions than transporting oil by rail.

WHAT DOES CANADA’S CARBON TAX POLICY LOOK LIKE?

Canada’s new “mandatory” carbon tax is complicated as some provinces have received special deals from Ottawa.

As of 2019, Canada’s federal government requires most provincial governments to charge a $20 per tonne carbon tax on carbon-based fuels (gasoline, aviation fuel, diesel, propane, etc.). This tax will rise to $50 per ton by 2022. (For a consumer putting gas in your car, this means the federal carbon tax will increase from 4.42 cents per litre to 11.05 cents per litre by 2022. To see the cost of the carbon tax for other fuels – click here.)

But as this Canadian Taxpayers Federation report notes, several provinces have been allowed to charge less costly carbon taxes: Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick. (Note: Alberta’s provincial carbon tax was cancelled after the May 2019 election, but the federal carbon tax will be charged in the province as of January, 2020.)

Another important note about the new federal carbon tax is that it’s charged in addition to all the other taxes Canadians regularly pay at the pump – federal excise taxes, provincial excise taxes, federal sales tax (GST), provincial sales tax, transit taxes, etc. Montreal leads the country with six different taxes on gasoline; some of which are charged on top of other taxes. See page 10 of this report to learn more about all the taxes on fuel – click here.

Why a carbon tax?

When it comes to options for reducing carbon dioxide emissions in Canada, many economists and pundits have expressed support for the concept of a carbon tax.

Proponents argue that by applying a tax on carbon-based fuels, consumers will seek alternative products and services that cost less. For example, if the carbon tax is high enough, a consumer might buy a fuel-efficient car instead of a gas guzzler, reducing the amount of fuel they have to purchase. Alternatively, he or she might take the bus, walk or ride their bicycle.

Proponents of carbon taxes often urge the reduction of other taxes to achieve revenue-neutrality for governments. This helps avoid situations where carbon taxes merely become a cash grab for governments, and this approach helps make the tax more palatable for the public.

In practice, there are a number of problems with the implementation of carbon taxes in Canada:

1) Carbon taxes affect our nation’s competitiveness. Forcing Canadian companies to pay a carbon tax, while their competitors in other countries do not have to pay such taxes, reduces the ability of many Canadian companies to compete internationally.

Consider the case of Citadel Drilling Inc. The oil well drilling firm decided to move three drilling rigs to the United States and noted the province’s carbon tax was a contributing factor.

In this case, the carbon tax hasn’t reduced Citadel Drilling’s emissions, it has merely helped shift them to the United States. As we share the same atmosphere, there has been no environmental gain.

At the same time, Canada lost jobs due in part to the carbon tax. Thus, Canada experienced economic pain without any environmental gain.

During a discussion with the Canadian Federation of Independent Business about the carbon tax’s effect on competitiveness, president Dan Kelly told us:

“It is a big deal that Canadian small businesses in the affected provinces are going to be less competitive relative to counterparts that operate in jurisdictions that don’t impose a carbon tax. Many of them are telling us, particularly comparing themselves to their U.S. counterpart that the prices of their products or services are going to have to rise, making Canadian companies less competitive, less able to win that contract and bring back those jobs…”

More broadly, when we hired Nanos Research to conduct some public opinion research on the carbon tax earlier this year, respondents were twice as likely (39%) to say the tax would make Canada’s business environment less competitive than those who responded it would make our economy more competitive (18%). To see our policy brief – click here.

The Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) has noted that current climate change measures in Canada would not meet the federal government’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. They estimate that Canada’s current carbon tax of $20 per tonne would need to reach $102 per tonne by 2030 to achieve the emission reduction targets (such a tax would be more than 22 cents per litre – in addition to other taxes on gasoline).

Ultimately, the PBO expects such a tax would create a drag on the economy, reducing GDP by 0.35% by 2030.

How carbon taxes affect Canada’s economy remains to be seen, but it can’t be ignored that our largest trading partner – the United States – has no plans to introduce such a tax.

Governments often try to help trade-exposed industries through various credits and subsidies, but it’s impossible to centrally plan our economy. Someone or some company will always be left behind.

2) Carbon taxes have not been revenue neutral in practice. Everywhere carbon taxes have been implemented in Canada, they have ended up costing taxpayers more than accompanying tax relief. Here is a good Sun column on the federal government’s “revenue neutral” carbon tax – click here. And while this CBC column suggests the federal carbon tax is currently revenue neutral, paragraphs three and four note that by 2023-24 the new tax will not be completely offset by tax reductions, some of the money will be used for grants to universities and hospitals – click here.

3) Carbon taxes are often introduced in lockstep with new regulations. A key argument put forward by proponents of carbon taxes is that they create a market mechanism to address the problem – tax the activity you’re trying to dissuade and consumers will choose less costly alternatives. At the same time, the market will respond with alternatives; no new regulations or government programs are needed.

However, Canadian politicians have routinely ignored that simple approach. Carbon taxes have routinely been accompanied by a myriad of new legislation and subsidy programs. One example of this would be Alberta’s carbon tax. The new tax was introduced alongside plans to phase out coal plants earlier than expected and subsidize the installation of light bulbs in people’s homes.

What about B.C.?

Proponents of carbon taxes often point to British Columbia as evidence that such taxes can be introduced without the sky falling.

Indeed, the B.C. government notes on its website, “between 2007 and 2016, provincial real GDP grew by 19%, while net emissions declined by 3.7%.”

But there are a few important points that readers may want to take note of concerning B.C.’s situation:

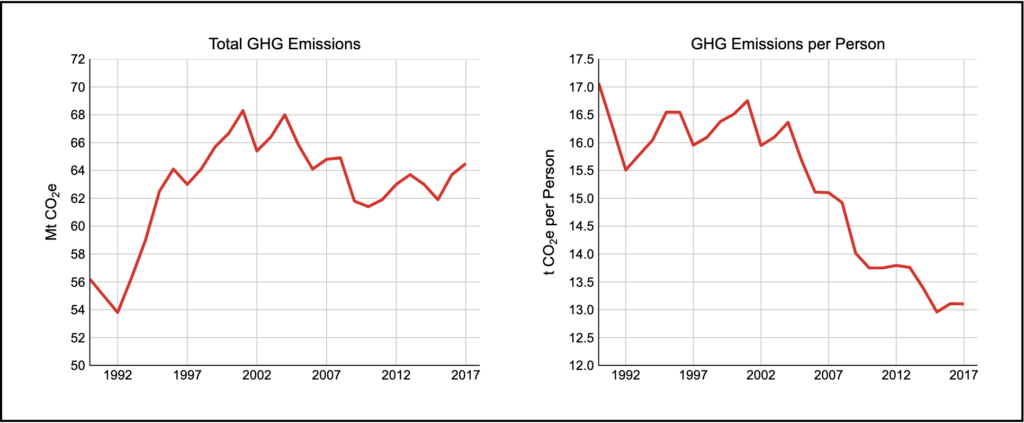

a) The government’s website shows B.C.’s total greenhouse gas emissions have been falling since 2004 – four years prior to the implementation of the carbon tax. Per capita emissions have also been dropping since the early 2000’s.

Thus, it seems there are likely other factors at play in British Columbia – technological change? A change in consumer preferences? Perhaps some carbon dioxide intensive activities have simply shifted to other locations rather than taking place in B.C.? It certainly seems as though B.C.’s situation is more complicated than the snapshot put forward by the government.

b) The government’s quote cited above covers the period 2007-2016. However, the government’s website includes a graph with data up until 2017 – a year later. If one includes the 2017 figures, total emissions in B.C. are roughly the same as they were in 2007 – before the carbon tax was implemented.

c) It’s true the sky has not fallen with the implementation of a carbon tax in British Columbia. However, it’s important to question what would have happened with B.C.’s economic growth if there hadn’t been a carbon tax? After all, the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer notes such taxes have a drag on economic growth. Would growth have been, say, 20% instead of 19%? Would it have been 22%? It’s hard to say.

And what would have happened with wages without a carbon tax? After all, every dollar that a business spends on the carbon tax is a dollar that can’t be spent on wages or benefits. These are important questions to consider – especially as the United States, our nation’s largest trading partner, does not appear to be introducing a carbon tax anytime soon.

Finally, it’s also important to note that while the sky hasn’t fallen in Canada after the implementation of a carbon tax, the tax is scheduled to increase from $20 per ton to $50 per ton over the next three years (150% increase). Every time the tax increases, it’s essentially another straw on the camel’s back (Canada’s business community). And if the tax increases to $100 per ton (as the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer suggests will be needed to meet emission targets), what kind of effect will that have on our economy?

4) HOW COULD TECHNOLOGY AFFECT THESE THREE ISSUES?

In 1898, government officials from several different cities gathered at the first urban planning conference in New York to discuss a very serious problem – the “Great Horse Manure Crisis.”

At the time, city streets around the world were full of horse and buggies transporting people and products all over the place. But those same streets also had a growing problem with horse manure, and in some cases, horse carcases laying on the roads for days at a time. All this culminated in an influx of flies that spread typhoid fever and other diseases.

Urban planners at the New York conference never did solve this problem. The issue was eventually addressed by technological change as cars replaced the horse and buggy.

As noted earlier, political parties across the spectrum in Canada have committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions – some also referring to today’s situation as a “crisis.” Development of our oil and gas resources and carbon tax policy are of course related issues that receive significant discourse in Canada.

Like we saw with the “great horse manure crisis,” technological change could once again address this environmental challenge and drastically affect all three of the aforementioned issues.

Electric cars are of course one of the most popular solutions to helping to reduce emissions. But as we noted in this blog post, such vehicles are full of parts and materials that are made with oil and gas products. Not to mention, those vehicles are often shipped to their dealerships using fossil fuels. While electric cars are starting to put a very small dent in vehicle sales, mass adoption still seems quite far off. Cost, charging times and availability of charging stations, as well as access to lithium for the vehicles’ batteries are all obstacles that need to be overcome.

But beyond electric cars, we’re seeing countless examples of companies coming forward with new technology to reduce emissions. Here are a few examples we have come across in Canada:

a) Ontario-based Pond Technologies has created a system that diverts carbon dioxide from smokestacks into large tanks that have algae inside. The algae then consume the carbon dioxide that’s pumped into the tanks and multiply. Ultimately, the algae can be processed and used to produce everything from animal feed and nutraceuticals to bioplastics and fertilizer.

b) Ontario-based Berg Chilling Systems has also developed technology that’s quite innovative. Their equipment reduces the amount of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that are burned at sites where oil and gas is extracted. Instead of oil companies burning methane and other gases when they extract oil and gas from the ground, Berg Chilling System’s equipment allows the companies to capture these gases and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

According to Berg’s site, just one of their units can reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 11,500 tons in a single year. Recently SecondStreet.org had a chance to speak with Berg Chilling about their product:

c) In the trucking world, companies such as Drivewyze have developed apps to help truck drivers with good safety track records to bypass weigh stations. By skipping these stops, the trucks don’t have to sit and waste fuel while staff weigh their vehicle and review their records.

d) Over the past 20 years, new technology has allowed the United States and Canada to substantially increase their natural gas supplies by tapping into deposits that have previously been considered uneconomical or too difficult to reach.

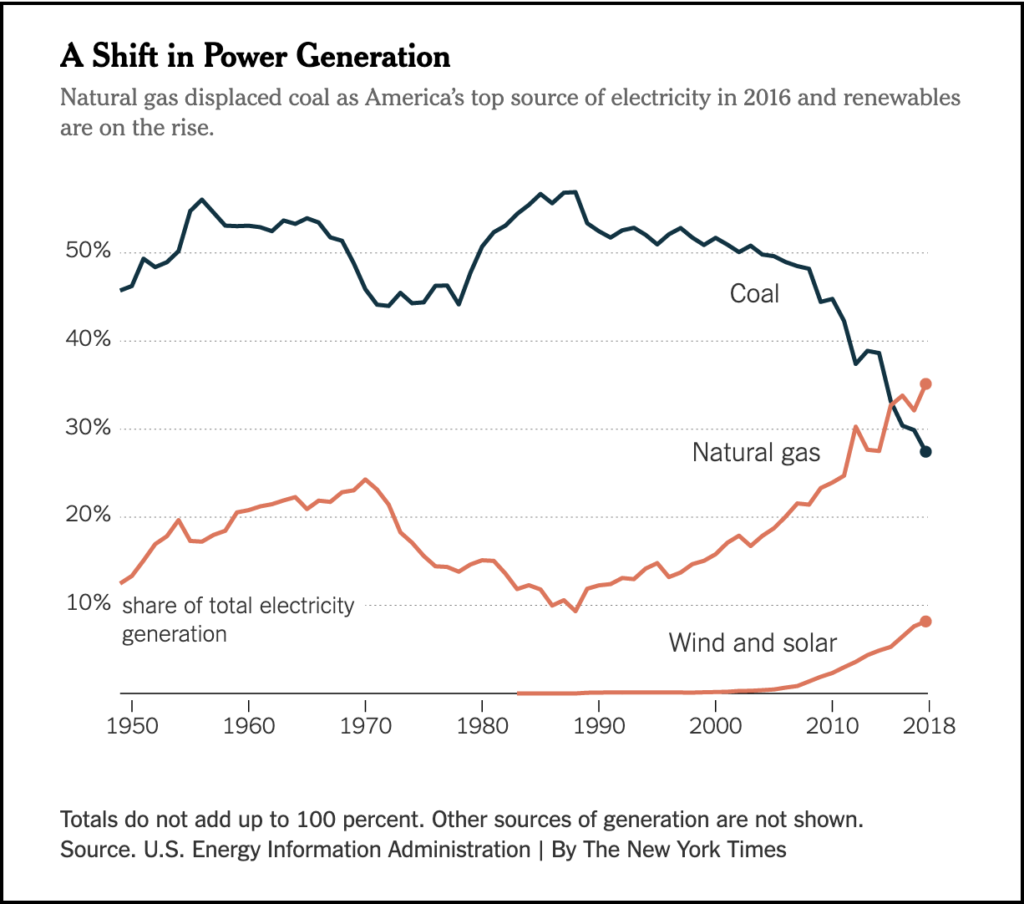

The increase in natural gas supplies has allowed electricity utilities in both countries to replace coal power with natural gas power. For instance, this New York Times graph shows that electricity from natural gas power plants has increased from about 10% of U.S. power supply in the late 1990s to over 30% as of 2018. At the same time, coal power dropped from over 50% of the nation’s electricity supply to less than 30%.

This is important from an emissions stand point as natural gas produces about half the carbon dioxide emissions that coal produces.

Other countries could also benefit from replacing their coal power with natural gas. For instance, according to WorldAtlas.com, China is the largest consumer of coal power in the world. Replacing their coal power with natural gas could not only reduce emissions, it could reduce the nation’s world-renowned smog problem as well.

Unfortunately, Canada has been slow to respond to China and other southeast Asian countries that have knocked on our door to purchase our natural gas. Other countries have stepped up much faster to sign contracts and build necessary infrastructure. Are there more LNG opportunities out there for Canada? Many analysts believe there are. If government regulatory roadblocks could be cleared this is another significant opportunity to help reduce global emissions.

CONCLUSION:

Without a doubt the aforementioned issues are complex and intertwined. Simply keeping Canadian oil in the ground will not help the environment and the situation is more complex than simply applying a carbon tax. At the same time, it seems unlikely that Canadian politicians will shrug their shoulders at climate change discourse and do nothing. But just as we saw with the “great horse manure crisis,” it seems technological change seems like the most likely solution. Indeed, we are already seeing several examples of new technology contributing to efforts to reduce emissions – including many advances by Canadian companies.

– Colin Craig, President of SecondStreet.org

Posted October 15, 2019